The events that occurred along the Jersey shore during a brutally hot summer in July 1916 may have signaled the start of our fascination with—and terror of—sharks.

It should be noted that although the attacks have been widely credited for inspiring Peter Benchley’s 1974 novel, Jaws, the author has said that they did not.1

1Correction. The New York Times. Sept. 8, 2001. http://www.nytimes.com/2001/09/08/nyregion/c-corrections-091162.html?pagewanted=all (Accessed Feb. 22, 2016).

SATURDAY, JULY 1: BEACH HAVEN

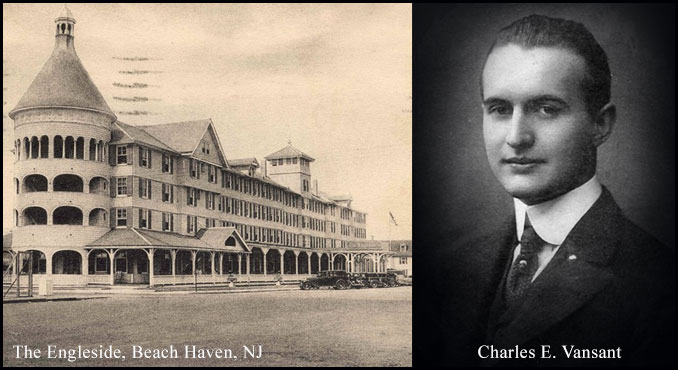

Approx. 5:00 pm: Charles Epting Vansant arrived in Beach Haven via train from Philadelphia, Pa., with his father and sisters in an attempt to escape the sweltering city heat and celebrate the holiday weekend. While his father and sisters went to the Engleside Hotel to unpack, Charles headed to the beach for a swim before dinner. Charles was a 25-year-old businessman who was known for his athleticism – he was on the golf and baseball teams in college – and outgoing personality.

Approx. 5:00 pm: Charles Epting Vansant arrived in Beach Haven via train from Philadelphia, Pa., with his father and sisters in an attempt to escape the sweltering city heat and celebrate the holiday weekend. While his father and sisters went to the Engleside Hotel to unpack, Charles headed to the beach for a swim before dinner. Charles was a 25-year-old businessman who was known for his athleticism – he was on the golf and baseball teams in college – and outgoing personality.

Approx. 6:00 pm: Charles was attacked by a shark approximately 50 yards from shore. Lifeguard Alexander Ott, a member of the 1910 American Olympic swim team, was the first to attempt to rescue Charles from the shark. (Subsequently, he also became the first lifeguard to perform such a duty – rescuing a swimmer from a shark attack – in American history.) It is reported by witnesses that the shark does not release him until he had been dragged by rescuers to water shallow enough for the shark to scrape its belly on the sand.

6:45 pm: Charles had been moved to the Engleside Hotel manager’s desk, where he passed away from blood loss.

Note: A sea captain witness claims the shark to be a sandpiper shark.

THURSDAY, JULY 6: SPRING LAKE

Charles Bruder was a 28-year-old Bell Captain at the Essex and Sussex Hotel in Spring Lake. Originally from Switzerland, Charles was supporting his mother, who was still living in Lucerna, Switzerland.

Charles Bruder was a 28-year-old Bell Captain at the Essex and Sussex Hotel in Spring Lake. Originally from Switzerland, Charles was supporting his mother, who was still living in Lucerna, Switzerland.

Approx. 1:45 pm: Charles took his lunch break with coworker Henry Nolan and they headed to the beach for their usual lunch-time swim.

Approx. 2:15 pm: Charles joined his friends in the surf in the employee section of the beach. A strong swimmer, Charles ventured farther out into the surf. Shortly afterward, he was attacked by a shark approximately 130 yards from shore. Lifeguards Chris Anderson and Capt. George White took a lifeboat out to rescue him and, as they reached him, Charles shouted to them that a shark bit off his legs. They pulled him into the boat and realized that both of his legs appeared to be gone below the knee. Charles passed away from severe blood loss while in the boat on the way to shore.

Charles is interred at the Atlantic View Cemetery in Manasquan.

SATURDAY, JULY 8: ASBURY PARK

WEDNESDAY, JULY 12: MATAWAN (6:30 AM)

The remains of the Wycoff dock along Matawan Creek was a popular swimming spot known for having a deep section, which made it a particularly attractive location for the town’s young boys to escape the oppressive heat of the summer (girls would not swim there). Located several miles inland from the ocean, it would have been absolutely unfathomable to Matawan residents that a shark could possibly be in the creek. The temperature that afternoon would reach 96 degrees.

The remains of the Wycoff dock along Matawan Creek was a popular swimming spot known for having a deep section, which made it a particularly attractive location for the town’s young boys to escape the oppressive heat of the summer (girls would not swim there). Located several miles inland from the ocean, it would have been absolutely unfathomable to Matawan residents that a shark could possibly be in the creek. The temperature that afternoon would reach 96 degrees.

That morning, the Coast Guard released a statement that there were “so many sharks [spotted along the shore] that a patrol of cutters would be useless.”

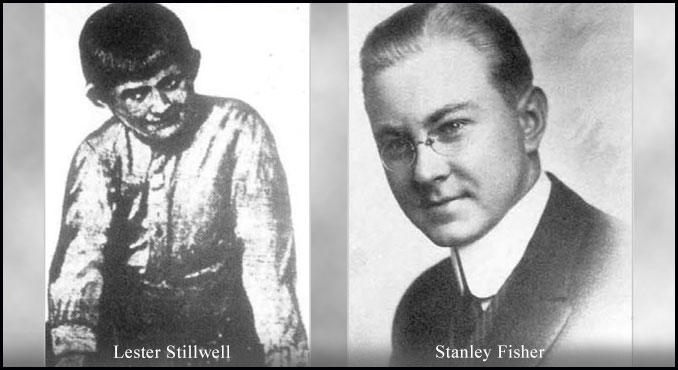

6:30 am: Lester Stillwell left for work with his father at Anderson Basket Factory. Lester’s best friend, Albert “Ally” O’Hara, also worked there. Lester was 11 years old and just one week shy of his 12th birthday. He suffered from tonic-clonic seizures due to epilepsy.

WEDNESDAY, JULY 12: MATAWAN (1:30 PM)

Capt. Cottrell ran to bridge keeper Welling’s booth, where there was a phone and called Mulsoff’s Barber Shop (John Mulsoff is the town barber and chief of police) to warn about the shark. However, Mulsoff doesn’t believe him and thinks it’s just a prank stemming from the attacks along the shore. Capt. Cottrell got in a boat to warn a group of boys heading toward the creek, but he missed both Lester’s group of friends and another group of boys swimming in the creek. He then ran up Main Street shouting the warning.

Around the same time, a motorboat of teen boys also saw the shark near the drawbridge. The boys in the boat were 18-year-olds Harold Conover, Ralph Gall, and John Tassini.

WEDNESDAY, JULY 12: MATAWAN (1:45 PM)

Approx. 1:50 pm: Capt. Cottrell runs through town, including past Stanley Fisher‘s shop and other businesses, shouting warnings about the shark. Still no one believed him.

Approx. 1:55 pm: The boat of teens warned Lester’s group of friends about the shark. According to Albert O’Hara, they thought it was a joke. 1

The group of boys swimming at the Wycoff dock: Lester Stillwell, Ally O’Hara, Charles Van Brunt, Johnson Cartan, Frank Close, Anthony Bubblin. [Local note: Johnson Cartan’s parents owned Cartan’s Department Store at 92 Main Street.]

About half a mile to the east, another group of boys was swimming by the brickyard docks: Joseph Dunn, Michael Dunn, Jerry Hourihan, plus two other friends.

Approx. 2:05 pm: Ally O’Hara felt a “sandpaper-like object graze his leg”; Lester floated to the deep section; Johnson Cartan and other boys saw what they said looked like an old log in the dark, muddy water; Anthony Bubblin did a back-flip into the water; just at that moment, Lester was attacked by the shark. The terrified boys fled the creek and ran naked and muddy up the street, screaming.

1 Fernicola, M.D., Richard G. (2001) Twelve Days of Terror (p. 296). Guilford, CT: The Lyons Press.

WEDNESDAY, JULY 12: MATAWAN (2:05 PM)

It was 30 minutes since Lester went under the water, but they still didn’t believe it was a shark attack. However, at this point, they knew they would not be finding Lester alive as he had been under water for too long, but they wanted to recover his body for his family. All three men changed into swim tights and dove in. Arthur Smith was scraped in the abdomen, which drew blood and left a scar. Mr. Burlew and Mr. Fisher, on the opposite side of the creek, had decided to stop diving.

By this time, a crowd had gathered at the creek’s banks, including Johnny Smith (Mr. Fisher’s assistant). Mr. Fisher decided to make one last dive to try to recover Lester’s body. Some witness claimed they saw Lester’s body briefly above the water’s surface as Mr. Fisher pulled him up from below. In waist-deep water, the shark attacked Mr. Fisher, who had to let go of Lester’s body. The athletic Mr. Fisher attempted to fight off the shark, striking it repeatedly and forcefully. However, the shark took him under the water’s surface twice and tore away a great deal of tissue from his thigh.

Witnesses to the event also included Arthur Van Buskirk (deputy at Monmouth Co. detective’s office in Keyport) and George Smith (Freehold detective), who had arrived in a motorboat just as the shark attacked Stanley. Mr. Van Buskirk hit the shark with an oar to get it to release Mr. Fisher.

Dr. George C. Reynolds was on the scene and attended to Mr. Fisher’s severed femoral artery. The decision was made to transport him via train to Long Branch Monmouth Memorial Hospital for treatment, but they would have to wait two hours at the railroad station for the next train.

WEDNESDAY, JULY 12: MATAWAN (2:35 PM)

Another group of children was swimming in the creek at the brickyard dock, about 1/2 mile to the east from the Wycoff dock. Joseph Dunn, a 12-year-old from New York City, was visiting his aunt in Cliffwood Beach with his brother Michael, who was 14 years old. Joseph and Michael joined their friend Jerry Hourihan and two other friends in the creek by the NJ Clay Co. docks.

Another group of children was swimming in the creek at the brickyard dock, about 1/2 mile to the east from the Wycoff dock. Joseph Dunn, a 12-year-old from New York City, was visiting his aunt in Cliffwood Beach with his brother Michael, who was 14 years old. Joseph and Michael joined their friend Jerry Hourihan and two other friends in the creek by the NJ Clay Co. docks.

The boys heard yelling and the word “shark” and quickly tried to make their way out of the creek. Joseph was farthest away from the dock ladder and last to reach it. He felt his left lower leg being bitten and he was pulled under. Michael and Jerry tried to pull him out, but it quickly became a tug-of-war between them and the shark. Robert Thress, the brickyard supervisor, heard the screams, ran over and pulled Joseph free. Jacob Lefferts, who was fishing nearby, jumped in the water to help.

Capt. Cottrell arrived in a motorboat and took Joeseph and Michael to the Wyckoff dock as he knew there were doctors there tending to Mr. Fisher. Dr. H.S. Cooley attended to Joseph, who was then driven to St. Peter’s Hospital in New Brunswick for further treatment.

WEDNESDAY, JULY 12: MATAWAN (5:06 PM)

5:30 pm: Mr. Fisher was wheeled into the operating room. Dr. Edwin Field was the surgeon working to save his life.

6:45 pm: Mr. Fisher died from blood loss and shock.

For more information about Stanley Fisher, please visit our Historic People page.

THURSDAY, JULY 13: MATAWAN

Arris B. Henderson, Matawan Mayor, posted a $100 reward for “killing the shark.”

FRIDAY, JULY 14: MATAWAN

5:30 am: Train conductor Harry Van Cleaf spots Lester Stillwell’s body floating in the creek by the train trestle (approx. 150 ft. west of Wycoff dock).

10:00 am: Stanley Fisher’s parents – who had been out of state visiting their daughter – arrive by train in Matawan.

SATURDAY, JULY 15: MATAWAN

Stanley Fisher and Lester Stillwell have separate funeral services. Both are interred at Rosehill Cemetery in Matawan.

Stanley Fisher and Lester Stillwell have separate funeral services. Both are interred at Rosehill Cemetery in Matawan.

The Fisher family used money from a life insurance policy ($7,500) Mr. Fisher had recently received – in exchange for work for a client – to purchase a stained glass window for the front of the Methodist Church. It was dedicated in July 1918 and damaged by a local blast five months later. In the 1970’s, the church was demolished and the window was auctioned off to the highest bidder to a private collector. Its current whereabouts are unknown.