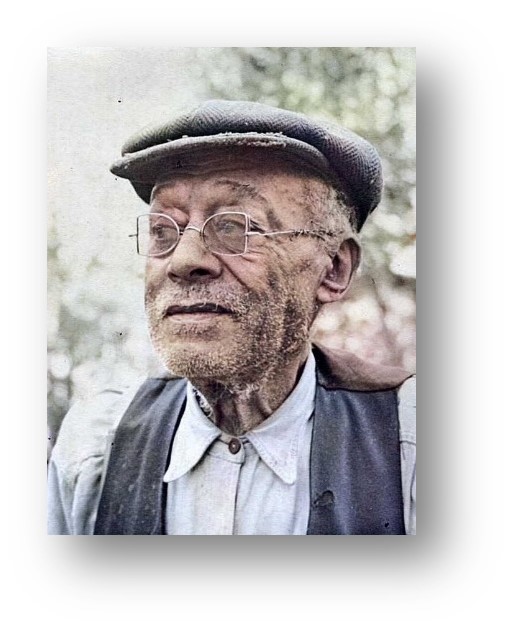

In 1985, a photograph of an elderly African American gentleman was donated to the Matawan Historical Society by the family of Myron Bradford Diggin (1904-1962). Simply entitled “Tom”, an inscription on the back of its matting indicated that “Tom” lived in the Matawan area and was “born a slave.” A label affixed to the image indicated it had won First Award at the Matawan Camera Club competition on April 21, 1938. An article in the Matawan Journal that date confirmed that Diggin had won the contest with this entry.

The 1930 Matawan census indicated that one Thomas Wicker, born in 1854 in Mississippi resided at 1 Franklin Street in the borough. Thomas Wicker led a remarkable life. The best way to relate his story is in a narrative format, starting in the 1850s in South Carolina.

African Americans in the 1850s were not enumerated in the general 1850 census – they had a separate “Slave Schedule” (this went for the Matawan area, too, wherein dozens were counted this way.) The schedule only noted the name of the owner, with a corresponding sex and age only – no names – of the slaves held.

The 1850 Slave Schedule for Newberry, SC listed slave owner Peter Asbury Wicker (1820-1892), a farmer, in possession of a single enslaved individual, a 15-year-old male. The 1860 census has Peter and his family relocated to Winston, MS – he was the only Wicker living in that town that year, and the corresponding Slave Schedule now indicated he owned four slaves – a male and female in their 20s, a 10 year old female and a five year old male. It is noted that freed slaves often took the surnames of their owners, and I believe the young male child probably is Tom Wicker.

The 1870 census in Winston lists the Frank Wicker family, African Americans. Frank was listed as being born in 1835 in South Carolina, which corresponds with the individual on the 1850 and 1860 Slave Schedules, above. His wife was Violet, also born in South Carolina in 1835 and five Wicker children, with Thomas at 14 – born in Mississippi – being the oldest.

I don’t think Frank was Thomas’ biological father, however – the census record indicates he was a “mulatto” while the other five children were listed as “black.” Violet was probably his mother, though. Unfortunately, this was a common occurrence – Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemmings comes to mind, and I just completed a DNA project wherein the DNA’s provider’s great grandfather was a slave holder, and I discovered the provider had an African American cousin whom I could trace to the ancestor.

The 1880 census places Thomas in Oktibbeha, MS – single, with a boarder Martha May and her two children Major May (5 years old) and Emma May (3). The Matawan 1895 census lists Thomas, wife Martha, Major, Emma and Lavinia all with the surname Wicker. The 1900 census has Thomas in Matawan on Franklin Street with Martha, Major and Emma and her husband George Carter, along with 16-year-old daughter Lavinia Wicker. The census indicated they had wed in 1875 and that Martha had given birth to four children, all of whom were still living in 1900. Thomas was employed as a farmer. The fourth child was determined to be Mary “Molly” Wicker – census and burial records indicate she was born around 1874 and it is unclear why she was not enumerated in the 1880 census with the family.

After 1880, the family most likely emigrated to Liberia, probably sponsored by the American Colonization Society (ACS). This apparently didn’t suit them, because they returned to the United States, arriving in New York from Monrovia, Liberia aboard the barque Liberia on July 8, 1892. Between that date and their 1895 census listing they settled in Matawan (a 1923 obituary for another Matawan resident, Watt Booker, indicated that Booker was part of the group with Thomas returning from Liberia that was stranded in New York City and subsequently settled in Matawan.)

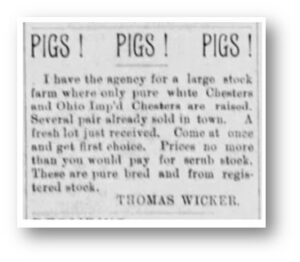

Wicker became involved in hog farming, advertising his pigs in the Matawan Journal on November 27, 1897. Matawan civic payments were also made to him over the years for street labor and the production of water valves. In 1898 he was appointed as Matawan’s pound keeper and in 1911 dog catcher – that year Matawan apparently started issuing dog licenses.

Wicker became involved in hog farming, advertising his pigs in the Matawan Journal on November 27, 1897. Matawan civic payments were also made to him over the years for street labor and the production of water valves. In 1898 he was appointed as Matawan’s pound keeper and in 1911 dog catcher – that year Matawan apparently started issuing dog licenses.

In 1903, Thomas purchased land for $300 from Sarah Wooley, lot #22 on the map of lots of Thomas I Bedle. Earlier maps show Bedle owning the land which is now Franklin Street. Later that year, Thomas became President of the newly formed Midway Green Cemetery Association. Wicker bought more property from Bedle in 1905 and 1908, and then in 1910 purchased 54 acres in Marlboro Township from Mary A. Thompson. In 1909, Thomas was elected Trustee of Matawan’s Second Baptist Church.

On August 20, 1911, a “colored camp” meeting was started on Wicker’s Texas Road property, which occurred each Sunday until September 17th. Led by the Reverend A. D. Davis and assisted by other ministers, the proceeds were to be applied for a home for the aged and an orphanage on the property. Wicker subsequently donated property on his tract for the Wicker Memorial Baptist Church which still operates on 180 Greenwood Road on the property.

While it’s unclear where Wicker’s first hog farm was – it may have been on the end of Franklin Avenue – he apparently moved his operation to his new acreage in Marlboro in 1916. In November of that year, the borough council reached out to him to see if he’d pick up the garbage in Matawan three times a week for his hogs. It’s unclear if he accepted this offer, which may have been Matawan’s attempt to establish uniform trash pickup.

Thomas died on June 25, 1939 and is buried with his wife and four children at Midway Green, the cemetery he established.

After his death, his son Major subdivided the Texas Road property as the Wicker Estates in 1942, one of Marlboro’s first developments. Located at Texas and Greenwood Roads, the streets were Wicker Place, Thomas Lane, Martha Place and Elizabeth Street (Martha’s middle name.) It is a mix of older and newer homes, with a substantial portion not yet developed.

From being stranded in New York City with a large family in 1892 after returning from Liberia with probably little or no resources, Thomas became a successful local entrepreneur who greatly assisted his community and deserves recognition. His family’s complete genealogy has been added to the Matawan Surname Project.

NO COMMENTS