The vacant J. L. Rue Pottery Company, which had been closed since 1895, offered an opportunity for Karl Wilhelm Mathiasen (1860-1920) and his brothers-in-law, the Eskesens, who wanted to expand their New Jersey Terra Cotta production facility in South Amboy. Matawan’s Henry Longstreet had known that the property and pottery production kilns would be attractive, due to the expanding terra cotta industry and the availability of quality clay in the area and purchased the property when it was auctioned.

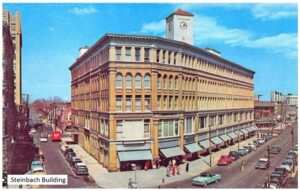

In January of 1897, the Matawan Terra Cotta Company was incorporated with a capital stock of $15,000 and leased the Rue property initially for five years. The board of directors consisted of Mathiasen as chairman, his wife’s younger brothers E.V. Eskesen, L.B. Eskesen, T. Eskesen, Bennet Eskesen, Jr, and Mathiasen’s wife’s younger sister’s husband, Peter Sondergaard. Karl would be the company’s president, L.B. the vice president and E.V. would be the firm’s secretary/treasurer. They immediately picked up contracts for architectural terra cotta, notably the new Steinbach Building in Asbury Park.  The initial work force was 21 with an expectation of doubling the size by that summer.

The initial work force was 21 with an expectation of doubling the size by that summer.

Upon acquisition, they immediately installed a new kiln. The company initially had an issue with obtaining clean water for their boilers – a well at the property at 258 feet produced a milky-colored water which wasn’t satisfactory. They eventually built a cistern to store clean water.

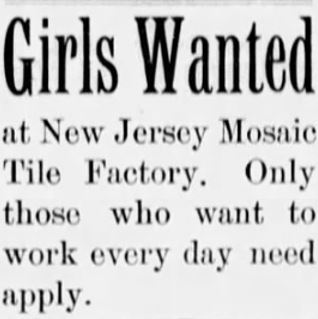

In 1901, the Matawan branch started making white, enameled tile and their South Amboy location continued with terra cotta products. Tile was gaining popularity in the country, primarily because of the construction of indoor bathrooms. They initially made 3” and 6” square pieces with the accompanying caps and molding. Production started at approximately 1000 square feet of product per day. Orders came in fast and they advertised for additional help in local newspapers.

In April of 1902, the company’s name was changed to The New Jersey Mosaic Tile Company of Matawan. That July, Henry Longstreet transferred 16 lots upon which the factory sat to the company. Two years later. Bennet Eskesen, Jr, built a beautiful residence at 98 Main Street which would remain standing until it was demolished for a gas station in the 1950s.

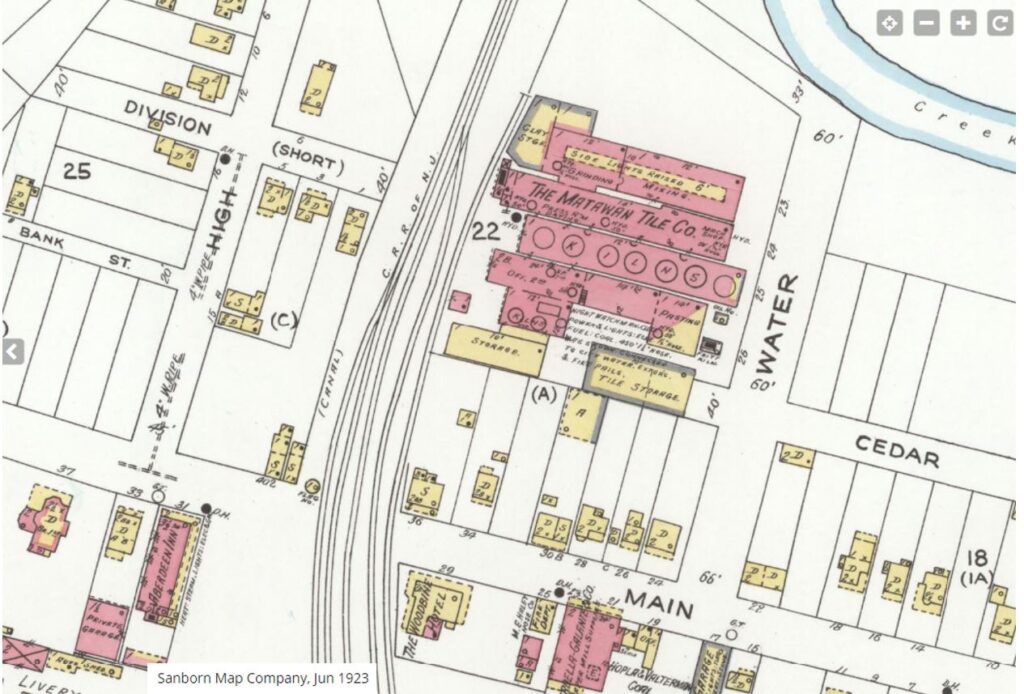

In January of 1905, the company was renamed The Matawan Tile Company. Karl Mathiasen was president, Bennet, Jr superintendent and E.V. Eskesen secretary and treasurer. They were assigned telephone #24-W and specialized in ceramic floor tile (a sister factory in Keyport made wall tile.) Necessary expansion included a new 50’ by 200’ building in 1907, and their work staff increased to over 100. Its stain-proof tile was in high demand and one customer was the State Agricultural College in Ithaca, NY, for their dairy department. Orders were filled from nearly every state in the country. The plants location adjacent to the railroad was a big factor in its success.

In April of 1908, Matawan Tile exhibited its product at the Historical and Industrial Exhibit in Asbury Park.

In 1913, the company closed its Keyport branch and moved its equipment to Matawan. Yet another large building was constructed on the site to accommodate the equipment and increased workforce.

As one might expect, there were serious injuries and death associated with an early 1900s, pre-OSHA manufacturing plant. On January 22, 1914, Lewis Tice, 46, was killed. Plants at the time had separate power plants, with belts, pulleys and drive shafts leading from them to power the various machines in different parts of the plant. Tice’s clothing was caught up in the mechanism. And he was pulled off the floor and “revolved with the machinery” until it was stopped. It was quite a horrific accident, and superintendent Eskesen was so overcome he had to be taken to his residence. That same week 20-year-old William Arnold fell through an elevator opening and was knocked unconscious, but eventually recovered. That December a boiler in the plant exploded and Simon Height, the engineer was burned, but not seriously. In October 1922, Camillo Sardello, 41, was killed when he lost control of a cart transporting tile and it crushed him. There were numerous reports over the years of non-fatal accidents at the plant.

One of Matawan’s largest fires in its history occurred on January 29, 1916 when Matawan Tile’s main manufacturing building and its contents caught fire and was destroyed, with the machine shop and kiln shed being significantly damaged. Matawan and Keyport FDs responded, with six streams of water being applied to fight the fire. Rebuilding started at once.

In April of 1921, Matawan Tile exhibited their work at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

In August of 1920, company president Karl Mathiasen died. He was a remarkable individual, and details of his life are presented in the Surname section.

In 1922, the Federal Government targeted Matawan Tile and 36 other tile and terra cotta firms for violation of the Sherman Anti-Trust Act. Authorities wanted prison sentences for E V Eskesen, but it didn’t happen.

In 1923, Asbury Park contracted with Matawan Tile to have them provide tile street signs for that community.

In May of 1924 the plant again expanded, with the new facilities occupied by the end of June. In November, the company bought the store and property of Thomas O’Heran, adjacent to the plant. O’Heran ran it as a lunchroom, and Matawan Tile planned to operate it as a restaurant run by Adolph Bauman. Chevy’s Cleaners now occupies this building.

Employees at the plant were active in Matawan civic affairs. During WWI, they were involved in the Red Cross and War Bond drives. They fielded a baseball team in the 1920s that played regional competitors for years.

In February of 1925, two new kilns were added to the facility, bringing the total to twelve. The company was supplying a high demand for decorative tile. Designers would sketch out patterns and the women working in the plant would glue small pieces of colored tile matching the pattern to a piece of paper. Contractors would then place the sheets on wet cement. When the material dried, the paper would be removed revealing the pattern.

The company was now at its apex, employing over 200 people. Their products were white only wall tile with associated caps, and multi-colored floor tile. The latter was made in all shapes and sizes. The chief ceramist was Theodore W. Drummond (1900-1969) of Matawan and Thomas Anthony Francy (1907-1989) supervised the factory.

Extensive improvements were again made in 1928. Residences on Main Street adjacent to the plant were bought and moved to lots purchased by the company in the Kane Terrace subdivision (quite a stir was made when one of the homes being moved on Main Street was simply left in the middle of the street when workmen “called it a day”.) They built a new structure on Main Street in their place which had fancy tile inlays and brickwork, and eventually housed companion firm The Progressive Art Tile Company. This structure now houses Aby’s Mexican Restaurant. They also built a new 56’ by 93’ facility along the railroad tracks. The buildings were completed in March of 1929.

In August of 1929, yet another devastating fire struck Matawan Tile. Flames broke out in the color-clay mixing department and spread throughout the facility. The Midway, Haley, Washington, Freneau and Cliffwood fire departments all responded, pumping water from Matawan Creek to fight the blaze. One major building was destroyed and president Bennet Eskesen, Jr, who was returning to Matawan on the midnight train, saw that the engine had stopped short of the station (hoses were across the track) and jumped off and ran to his factory. Seventy five percent of the work force was able to return to work the following day. Within two weeks, a decision was made to replace the destroyed structure with a new, two story brick building.

In August of 1930, Matawan Tile merged its sales department with that of the much larger C. Pardee Tile firm of Perth Amboy. The Progressive Art Tile company also was involved in this merger (Progressive was a wholly owned subsidiary of Matawan Tile, with Bennet Eskesen, Jr, president and Harry Kahn, VP.). The new arrangement would handle sales for both companies. In April of 1931, the Pardee-Matawan Tile Company announced it had secured contracts to supply 100,000 square feet of wall and floor tile for six New York City apartment complexes. Matawan Tile had a separate contract that month for 40,000 square feet of tile for the Hillsdale Sanitarium.

During the depression, the company didn’t operate for a period, during which several employees of the larger local tile companies produced art tile out of their residences.

Matawan Tile experienced labor disputes in 1937. In March, a 2 cents per hour raise was granted in the Perth Amboy plant after 140 workers staged a sit-down strike. Union workers organized in Matawan in May, and then in July those workers went on strike, called by the Tile Workers Union #20851. They demanded a 15 cents per hour raise (the pay rate had been 40 cents an hour), seniority rights, and the ability for having the union have a say in the termination of employees. The company countered with a 2-cent raise, agreed to the seniority issue, but refused to let the unions interfere with the termination of employee process. After two weeks, the strike ended, with the employees getting a 2 cent raise and a proposed compromise on the termination issue.

In December of 1937, the agreement with Pardee was terminated and Matawan and Progressive resumed their own marketing operations.

In April of 1938, the new Matawan Post Office opened, with tile for the building furnished by Matawan Tile.

In August of 1938, the Federal Trade Commission accused three firms, including Matawan Tile, for price discrimination. It dismissed these complaints in 1941.

A newspaper article noted that because Matawan Tile was unable to convert to war industry in WWII, it shut down its operation. In August of 1941, the Keyport Weekly noted that Matawan Tile, after labor negotiations, granted pay raises to its employees. I noted a March 1942 wedding announcement which indicated that the bride was currently employed by the company, so it was apparently in business at that time. In December of 1943, however, a tax sale was held for some of its real estate, and subsequent articles referred to the property as “the former site of Matawan Tile.”

Companies come and go, but Matawan Tile, and its Progressive Art Tile subsidy, left a lasting gift to its community – the beautiful art tile it produced which is now highly collectable. Additionally, standing structures across the country used unmarked Matawan Tile in their construction. Mosaics carefully crafted by the women of Matawan, following patterns provided by the company’s artists, must decorate countless structures whose identities cannot be determined.

I contacted MJ Kahn, the granddaughter of Progressive Art Tile vice president Harry Kahn, whose father John is still alive. John was a young child who grew up on Schenck Avenue in the 1930s. Not only was Harry Progressive’s VP, his wife Hannah designed the tiles. A picture of four is shown here.  I have a similar piece attributed to Progressive (next to the four in the picture), Mine isn’t marked “Progressive”, though, and the possibility is that none are.

I have a similar piece attributed to Progressive (next to the four in the picture), Mine isn’t marked “Progressive”, though, and the possibility is that none are.

Matawan Tiles, though, are marked. Their distinctive octagonal shape makes them highly recognizable. The Matawan Historical Society has a collection of these at Burrowes Mansion, and the picture of the five comes from my personal collection.

NO COMMENTS